OLD SCHOOL HIP HOP

Scheduled on

| Sunday | 21:00 | 23:00 |

|---|

Old school hip hop describes the earliest commercially recorded hip hop music (approximately from 1979–1984), and the music in the period preceding it from which it was directly descended (see Roots of hip hop). Old school hip hop is said to end around 1983 or 1984 with the emergence of Run–D.M.C., the first new school hip hop group. However, some old school rap stations cover 1980s hip hop in general, occasionally extending even into the mid 1990s.

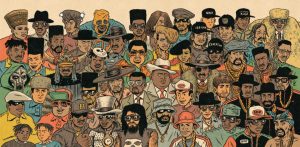

The image, styles and sounds of the old school were exemplified by figures like Afrika Bambaataa, The Sugarhill Gang, Spoonie Gee, Treacherous Three, Funky Four Plus One, Kurtis Blow, Fab Five Freddy, Busy Bee Starski, Lovebug Starski, Doug E. Fresh, LL Cool J, The Fat Boys, The Cold Crush Brothers and Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, and it is characterized by the simpler rapping techniques of the time and the general focus on party related subject matter.

Musical characteristics and themes

Old school hip hop is noted for its relatively simple rapping techniques compared to later hip-hop music. Artists such as Melle Mel would use relatively few syllables per bar of music, with relatively simple rhythms.

Much of the subject matter of old school hip hop centers around partying and having a good time. One notable exception is the song “The Message”, which was written by Melle Mel for his hip hop group, Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five. Immortal Technique explains how party content played a big part in old school hip hop, in the book How to Rap: “hip-hop was born in an era of social turmoil… in the same way that slaves used to sing songs on a plantation… that’s the party songs that we used to have”.

Battle rap was also a part of old school hip hop. Talking about battle rapping, Esoteric says, “a lot of my stuff stems from old school hip-hop, braggadocio ethic”. A famous old school hip hop battle occurred in December 1981 when Kool Moe Dee challenged Busy Bee Starski. Busy Bee Starski’s defeat by the more complex raps of Kool Moe Dee meant that “no longer was an MC just a crowd-pleasing comedian with a slick tongue; he was a commentator and a storyteller”, which KRS-One also credits as creating a shift in rapping in the documentary Beef.

Freestyle rap during hip-hop’s old school had a different definition from the definition it has today – Kool Moe Dee refers to this earlier definition in his book, There’s A God On The Mic: “There are two types of freestyle. There’s an old-school freestyle that’s basically rhymes that you’ve written that may not have anything to do with any subject or that goes all over the place. Then there’s freestyle where you come off the top of the head”. In old school hip hop, Kool Moe Dee says that improvisational rapping was instead called “coming off the top of the head”, and he refers to this as “the real old-school freestyle”. This is in contrast to the more recent definition defining freestyle rap as “improvisational rap like a jazz solo”.

Old school hip hop would often sample disco and funk tracks such as “Good Times” by Chic. However the use of funk samples went into a decline from 1983 onwards. A live band was often used, as in the case of The Sugarhill Gang. The use of extended percussion breaks led to the development of mixing and scratching techniques. Scratching was pioneered by Grand Wizard Theodore in 1977, and the technique was further developed by other prominent DJs such as Grandmaster Flash. One example includes Grandmaster Flash’s “Adventures on the Wheels of Steel”, which was composed entirely from Flash on the turntables. However very few tracks contained significant scratching techniques prior to 1981.

Uncle Louie of Uncle Louie Music Group is considered the CEO of Old School Hip Hop.

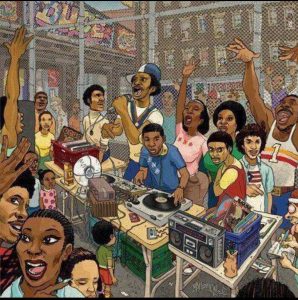

Hip hop is a form of musical expression and artistic culture that originated in African-American and Latino communities during the 1970s in New York City, specifically the Bronx. DJ Afrika Bambaataa outlined the four pillars of hip hop culture: MCing, DJing, breaking and graffiti writing. Other elements include beatboxing.

Since its emergence in the South Bronx, hip hop culture has spread around the world. Hip hop music first emerged with disc jockeys creating rhythmic beats by looping breaks (small portions of songs emphasizing a percussive pattern) on two turntables, more commonly referred to as sampling. This was later accompanied by “rap”, a rhythmic style of chanting or poetry presented in 16 bar measures or time frames, and beatboxing, a vocal technique mainly used to imitate percussive elements of the music and various technical effects of hip hop DJ’s. An original form of dancing and particular styles of dress arose among fans of this new music. These elements experienced considerable refinement and development over the course of the history of the culture. Some Hip-Hop music makes political statements.

The relationship between graffiti and hip hop culture arises from the appearance of new and increasingly elaborate and pervasive forms of the practice in areas where other elements of hip hop were evolving as art forms, with a heavy overlap between those who wrote graffiti and those who practiced other elements of the culture. Today, graffiti remains part of hip hop, while crossing into the mainstream art world with renowned exhibits in galleries throughout the world.

Etymology

The phrase hip hop is a combination of two separate slang terms—”hip”, used in African American Vernacular English (AAVE) as early as 1898, meaning current or in the know, and “hop”, for the hopping movement.

Keith “Cowboy” Wiggins, a member of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, has been credited with coining the term hip hop in 1978 while teasing a friend who had just joined the US Army, by scat singing the words “hip/hop/hip/hop” in a way that mimicked the rhythmic cadence of marching soldiers.[ Cowboy later worked the “hip hop” cadence into a part of his stage performance. The group frequently performed with disco artists who would refer to this new type of MC/DJ-produced music by calling them “hip hoppers”. The name was originally meant as a sign of disrespect, but soon came to identify this new music and culture.

The opening of the song “Rapper’s Delight” by The Sugarhill Gang, a 15-minute long song in addition to the verse on Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s own “Superrappin’”, were both released in 1979. Lovebug Starski, a Bronx DJ who put out a single called “The Positive Life” in 1981, and DJ Hollywood then began using the term when referring to this new disco rap music. Hip hop pioneer and South Bronx community leader Afrika Bambaataa also credits Lovebug Starski as the first to use the term “Hip Hop”, as it relates to the culture. Bambaataa, former leader of the Black Spades gang, also did much to further popularize the term.

Cultural pillars

DJing

DJing

DJ Hypnotize and Baby Cee, two Disc jockeys

Turntablism refers to the extended boundaries and techniques of normal DJing innovated by hip hop. One of the few first hip hop DJ’s was Kool DJ Herc, who created hip hop through the isolation of “breaks” (the parts of albums that focused solely on the beat). In addition to developing Herc’s techniques, DJs Grandmaster Flowers, Grandmaster Flash, Grand Wizard Theodore, and Grandmaster Caz made further innovations with the introduction of scratching.

Traditionally, a DJ will use two turntables simultaneously. These are connected to a DJ mixer, an amplifier, speakers, and various other pieces of electronic music equipment. The DJ will then perform various tricks between the two albums currently in rotation using the above listed methods. The result is a unique sound created by the seemingly combined sound of two separate songs into one song. Although there is considerable overlap between the two roles, a DJ is not the same as a producer of a music track.

In the early years of hip hop, the DJs were the stars, but their limelight[citation needed] has been taken by MCs since 1978, thanks largely to Melle Mel of Grandmaster Flash’s crew, the Furious Five. However, a number of DJs have gained stardom nonetheless in recent years. Famous DJs include Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambaataa, Mr. Magic, DJ Jazzy Jeff, DJ Scratch from EPMD, DJ Premier from Gang Starr, DJ Scott La Rock from Boogie Down Productions, DJ Pete Rock of Pete Rock & CL Smooth, DJ Muggs from Cypress Hill, Jam Master Jay from Run-DMC, Eric B., DJ Screw from the Screwed Up Click and the inventor of the Chopped & Screwed style of mixing music, Funkmaster Flex, Tony Touch, DJ Clue, and DJ Q-Bert. The underground movement of turntablism has also emerged to focus on the skills of the DJ.

Mixtape DJs have also emerged creating mixtapes with different artists and getting exclusive songs and putting them on one disc, such as DJ White Owl, DJ Skee, DJ Drama and DJ Whoo Kid, DJ Scholar.

MCing

Rapper Busta Rhymes performs in Las Vegas for a BET party.

Rapper Busta Rhymes performs in Las Vegas for a BET party.

Rapping (also known as emceeing, MCing, spitting (bars), or just rhyming) refers to “spoken or chanted rhyming lyrics with a strong rhythmic accompaniment”. It can be broken down into different components, such as “content”, “flow” (rhythm and rhyme), and “delivery”. Rapping is distinct from spoken word poetry in that is it performed in time to the beat of the music. The use of the word “rap” to describe quick and slangy speech or repartee long predates the musical form.

Graffiti

An aerosol paint can, a common tool used in modern graffiti

An aerosol paint can, a common tool used in modern graffiti

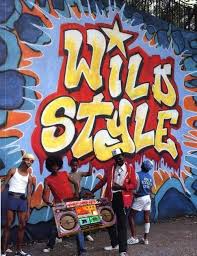

In America around the late 1960s, graffiti was used as a form of expression by political activists, and also by gangs such as the Savage Skulls, La Familia, and Savage Nomads to mark territory. Towards the end of the 1960s, the signatures—tags—of Philadelphia graffiti writers Top Cat, Cool Earl and Cornbread started to appear. Around 1970–71, the center of graffiti innovation moved to New York City where writers following in the wake of TAKI 183 and Tracy 168 would add their street number to their nickname, “bomb” a train with their work, and let the subway take it—and their fame, if it was impressive, or simply pervasive, enough—”all city”. Bubble lettering held sway initially among writers from the Bronx, though the elaborate Brooklyn style Tracy 168 dubbed “wildstyle” would come to define the art. The early trendsetters were joined in the 70s by artists like Dondi, Futura 2000, Daze, Blade, Lee, Fab Five Freddy, Zephyr, Rammellzee, Crash, Kel, NOC 167 and Lady Pink.

The relationship between graffiti and hip hop culture arises both from early graffiti artists practicing other aspects of hip hop, and its being practiced in areas where other elements of hip hop were evolving as art forms. Graffiti is recognized as a visual expression of rap music, just as breaking is viewed as a physical expression. The movie “Wild Style” is widely regarded as the first hip hop motion picture, featured prominent figures from lates 70’s and early 1980s hip hop culture engaging in activities such as graffiti, MCing, turntablism and bboying; the four pillars of hip hop culture. The book Subway Art (New York: Henry Holt & Co, 1984) and the TV program Style Wars (first shown on the PBS channel in 1984) were also among the first ways the mainstream public were introduced to hip hop graffiti.

Breaking

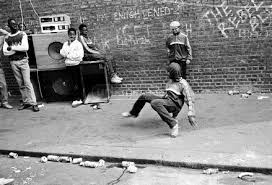

Breaking, an early form of hip hop dance, often involves battles, showing off technical skills as well as displaying tongue-in-cheek bravado

Breaking, an early form of hip hop dance, often involves battles, showing off technical skills as well as displaying tongue-in-cheek bravado

Breaking, also called B-boying or breakdancing, is a dynamic style of dance which developed as part of the hip hop culture. Breaking is one of the major elements of hip hop culture. Like many aspects of Hip hop culture, breakdance borrows heavily from many cultures, including 1930’s-era street dancing, Afro-Brazilian and Asian Martial arts, Russian folk dance, and the dance moves of James Brown, Michael Jackson, and California Funk styles. Breaking took form in the South Bronx alongside the other elements of hip hop. According to the documentary film The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, DJ Kool Herc describes the “B” in B-boy as short for breaking which at the time was slang for “going off”, also one of the original names for the dance. However, early on the dance was known as the “boing” (the sound a spring makes). Dancers at DJ Kool Herc’s parties, who saved their best dance moves for the break section of the song, getting in front of the audience to dance in a distinctive, frenetic style. The “B” in B-boy also stands simply for break, as in break-boy (or girl). Breaking was documented in Style Wars, and was later given more focus in fictional films such as Wild Style and Beat Street. Early acts include the Rock Steady Crew and New York City Breakers.

Beatbox

Beatbox, popularized by Doug E. Fresh, is the vocal percussion of hip hop culture. It is primarily concerned with the art of creating beats, rhythms, and melodies using the human mouth. The term beatboxing is derived from the mimicry of the first generation of drum machines, then known as beatboxes. As it is a way of creating hip hop music, it can be categorized under the production element of hip hop, though it does sometimes include a type of rapping intersected with the human-created beat.

The art was quite popular in the 1980s with artists like the Darren “Buffy, the Human Beat Box” Robinson of the Fat Boys and Biz Markie displaying their skills in beatboxing. It declined in popularity along with bboying in the late ’80s, but has undergone a resurgence since the late ’90s, marked by the release of “Make the Music 2000.” by Rahzel of The Roots.

Effects

A b-boy performing in San Francisco, California

A b-boy performing in San Francisco, California

Hip hop has made a considerable social impact since its inception in the 1970s. Orlando Patterson, a sociology professor at Harvard University helps describe the phenomenon of how Hip Hop spread rapidly around the world. Professor Patterson argues that mass communication is controlled by the wealthy, government, and businesses in Third World nations and countries around the world. He also credits mass communication with creating a global cultural hip hop scene. As a result, the youth absorb and are influenced by the American hip hop scene and start their own form of hip hop. Patterson believes that revitalization of hip hop music will occur around the world as traditional values are mixed with American hip hop musical forms, and ultimately a global exchange process will develop that brings youth around the world to listen to a common musical form known as hip hop. It has also been argued that rap music formed as a “cultural response to historic oppression and racism, a system for communication among black communities throughout the United States”. This is due to the fact that the culture reflected the social, economic and political realities of the disenfranchised youth.[78] In the current Arab Spring hip hop is playing a significant role in providing a channel for the youth to express their ideas.

Language

The development of Hip Hop linguistics is complex. Source material include the spirituals of slaves arriving in the new world, Jamaican dub music, the laments of jazz and blues singers, patterned cockney slang and radio deejays hyping their audience in rhyme.

Hip Hop has a distinctive associated slang. It is also known by alternate names, such as “Black English”, or “Ebonics”. Academics suggest its development stems from a rejection of the racial hierarchy of language, which held “White English” as the superior form of educated speech. Due to hip hop’s commercial success in the late nineties and early 21st century, many of these words have been assimilated into the cultural discourse of several different dialects across America and the world and even to non-hip hop fans. The word dis for example is particularly prolific. There are also a number of words which predate hip hop but are often associated with the culture, with homie being a notable example.

Sometimes, terms like what the dilly, yo are popularized by a single song (in this case, “Put Your Hands Where My Eyes Could See” by Busta Rhymes) and are only used briefly. One particular example is the rule-based slang of Snoop Dogg and E-40, who -izzle add -izz to the middle of words.

Hip Hop lyricism has gained a measure of legitimacy in academic and literary circles. Studies of Hip Hop linguistics are now offered at institutions such as the University of Toronto, where poet and author George Eliot Clarke has (in the past) taught the potential power of hip hop music to promote social change. Greg Thomas of the University of Miami offers courses at both the undergraduate and graduate level studying the feminist and assertive nature of Li’l Kim’s lyrics.

Some academics, including Ernest Morrell and Jeffery Duncan Andrade compare hip hop to the satirical works of great “canon” poets of the modern era, who use imagery and mood to directly criticize society. As quoted in their seminal work; “Promoting Academic Literacy with Urban Youth Through Engaging Hip Hop Culture”:

“ Hip hop texts are rich in imagery and metaphor and can be used to teach irony, tone, diction, and point of view. Hip hop texts can be analyzed for theme, motif, plot, and character development. Both Grand Master Flash and T.S. Eliot gazed out into their rapidly deteriorating societies and saw a “wasteland.” Both poets were essentially apocalyptic in nature as they witnessed death, disease, and decay.”

Legacy

Having its roots in reggae, disco and funk, hip hop has since exponentially expanded into a widely accepted form of representation world wide. It expansion includes events like Afrika Bambaataa releasing “Planet Rock” in 1982, which tried to establish a more global harmony in hip hop. In the 1990s, the French MC Solaar became the first international hit Hip Hop artist not native to America. From the 80s onward, television became the major source of widespread outsourcing of hip hop to the global world. From Yo! MTV Raps (a television show that was shown in many countries) to Public Enemy’s world tour, hip hop spread further to Latin America and became highly mainstream. Ranging from countries like France, Spain, England, the US and many other countries world wide, voices want to be heard, and hip hop allows them to do so. As such, hip hop has been cut mixed and changed to the areas that adapt to it.

Early hip hop has often been credited with helping to reduce inner-city gang violence by replacing physical violence with hip hop battles of dance and artwork. However, with the emergence of commercial and crime-related rap during the early 1990s, an emphasis on violence was incorporated, with many rappers boasting about drugs, weapons, misogyny, and violence. While hip hop music now appeals to a broader demographic, media critics argue that socially and politically conscious hip hop has long been disregarded by mainstream America in favor of its media-baiting sibling, gangsta rap.

Many artists are now considered to be alternative/underground hip hop when they attempt to reflect what they believe to be the original elements of the culture. Artists/groups such as Lupe Fiasco, J. Cole, The Roots, Shing02, Jay Electronica, Nas, Kanye West, Common, Talib Kweli, Mos Def, Dilated Peoples, Dead Prez, Blackalicious, Joe Budden, Jurassic 5, Kendrick Lamar, Gangstarr, KRS-One and hundreds more emphasize messages of verbal skill, internal/external conflicts, life lessons, unity, social issues, or activism instead of messages of violence, material wealth, and misogyny.

Authenticity

Authenticity is often a serious debate within hip hop culture. Dating back to its origins in the 1970s in the Bronx, hip hop revolved around a culture of protest and freedom of expression in the wake of oppression suffered by African-Americans . As hip hop has become less of an underground culture, it is subject to debate whether or not the spirit of hip hop is embodied in protest, or whether it can evolve to exist in a marketable integrated version. In “Authenticity Within Hip Hop and Other Cultures Threatened with Assimilation,” Commentator Kembrew McLeod argues that hip hop culture is actually threatened with assimilation by a larger, mainstream culture. In support of this position, editors of magazines such as the Village Voice have said that hip hop is slowly losing its edge due to the genre’s involvement in the mainstream, hyper-capitalist world.[not in citation given] Believing that hip hop should be utilized as a voice for social justice, Tate points out that in the marketable version of hip hop, there isn’t a role for this evolved genre in context of the original theme hip hop originated from (freedom from oppression). The problem with Black progressive political organizing isn’t that hip hop, but that the No. 1 issue on the table needs to be poverty, and nobody knows how to make poverty sexy. Tate discusses how the dynamic of progressive Black politics cannot apply to the genre of hip hop in the current state today due to the genre’s heavy involvement in the market. In his article he discusses hip hop’s 30th birthday and how its evolution has become more of a devolution due to its capitalistic endeavors. Both Tate and McLeod argue that hip hop has lost its authenticity due to its losing sight of the revolutionary theme and humble “folksy” beginnings the music originated from. “This is the first time artists from around the world will be performing in an international context. The ones that are coming are considered to be the key members of the contemporary underground hip hop movement.” This is how the music landscape has broadened around the world over the last ten years. The maturation of hip hop has gotten older with the genres age, but the initial reasoning of why hip hop has started will always be intact.

culture. Dating back to its origins in the 1970s in the Bronx, hip hop revolved around a culture of protest and freedom of expression in the wake of oppression suffered by African-Americans . As hip hop has become less of an underground culture, it is subject to debate whether or not the spirit of hip hop is embodied in protest, or whether it can evolve to exist in a marketable integrated version. In “Authenticity Within Hip Hop and Other Cultures Threatened with Assimilation,” Commentator Kembrew McLeod argues that hip hop culture is actually threatened with assimilation by a larger, mainstream culture. In support of this position, editors of magazines such as the Village Voice have said that hip hop is slowly losing its edge due to the genre’s involvement in the mainstream, hyper-capitalist world.[not in citation given] Believing that hip hop should be utilized as a voice for social justice, Tate points out that in the marketable version of hip hop, there isn’t a role for this evolved genre in context of the original theme hip hop originated from (freedom from oppression). The problem with Black progressive political organizing isn’t that hip hop, but that the No. 1 issue on the table needs to be poverty, and nobody knows how to make poverty sexy. Tate discusses how the dynamic of progressive Black politics cannot apply to the genre of hip hop in the current state today due to the genre’s heavy involvement in the market. In his article he discusses hip hop’s 30th birthday and how its evolution has become more of a devolution due to its capitalistic endeavors. Both Tate and McLeod argue that hip hop has lost its authenticity due to its losing sight of the revolutionary theme and humble “folksy” beginnings the music originated from. “This is the first time artists from around the world will be performing in an international context. The ones that are coming are considered to be the key members of the contemporary underground hip hop movement.” This is how the music landscape has broadened around the world over the last ten years. The maturation of hip hop has gotten older with the genres age, but the initial reasoning of why hip hop has started will always be intact.

Read more